The Aquaculture lectorate is the longest functioning research group of the HZ. It has built up years of expertise in research into low-trophic aquaculture, that is to say aquaculture of organisms that are low in the food chain, such as algae, seaweed and shellfish. In collaboration with the Zeeland shellfish sector, government and other research institutes, the lectorate carries out its practice-oriented research. HZ Discovery discussed five projects with coordinator Pascalle Jacobs that provide a good picture of the current research portfolio.

Oyster reef restoration

The Aquaculture lectorate participates in two projects that aim to restore flat oyster banks or reefs. The aim of these projects is twofold: nature restoration and improvement of flat oyster farming. The native flat oyster (Ostrea edulis) used to be ubiquitous in Northern European waters, including Zeeland. Overfishing led to the virtual disappearance of wild oyster populations in the mid-19th century and to the rise of oyster farming as an alternative to wild catch. However, flat oyster farming is not going well; it has been declining in the Netherlands for years, partly due to the lack of oyster larvae in the water.

Wild oyster banks or reefs represent important natural values. Firstly, due to the ability of oysters to filter large quantities of water and thus remove fertilisers. Furthermore, an oyster reef increases biodiversity because it is a habitat for many marine species, including commercially interesting species such as lobster and eel. Finally, an oyster reef produces larvae that are released into the water column and that form the starting material for breeding. Restoring natural oyster beds, the idea is, is therefore good for both nature and the economy.

A pilot project has been started in the Veerse Meer to create an oyster reef made of baked stone blocks with flat oyster larvae on them. The larvae have settled in breeding basins on the blocks. These breeding basins are located at the Zeeschelp foundation, which is the only foundation in the Netherlands that is able to grow flat oysters in the laboratory year after year. Once dumped in the Veerse Meer, the blocks will fall apart in a few years while the oysters simultaneously form a stable reef. This method was developed by Oyster Heaven, a ‘start-up’ that wants to create oyster reefs on a large scale in the coming years to increase biodiversity and water quality in the North Sea, for example. In the coming years, the growth of the oyster reef and the development of biodiversity in and near the reef will be monitored.

The Aquaculture lectorate is a knowledge partner and conducts research in the lab into predation and anoxia, two factors that influence the success of oyster restoration. “A student is looking at whether there is a difference in predation of oyster larvae by crabs on the blocks compared to the bottom,” Pascalle Jacobs explains. “Another student has built an ingenious setup to measure the effect of oxygen deficiency on survival. The lack of oxygen is particularly important in some deeper parts of the Grevelingen and that is important for the growers for whom we do a lot of research.”

Another project that also involves the construction of a reef of flat oysters is interesting enough to mention here, even though it is still in the subsidy application phase at RAAK-pro. The idea was developed after a visit by French colleagues to oyster farmers in Yerseke. Pascalle Jacobs: “They told us that they were struggling with the same problems as here, namely that they counted fewer oyster larvae in the water every year, which put their production at risk. At one point, the farmers agreed to dump five percent of their cultivated oysters in a place in the sea. They took good care of those oysters by catching the predators. The oysters grew and started producing offspring. After a few years, the number of oyster larvae increased significantly again.” The oyster farmers here wanted that too, and that is how the plan came about to create a reef of flat oysters in the Oosterschelde that will become a nursery for new oyster brood.

Oysters differ from other shellfish in their reproduction, as they do not bring their egg and sperm cells into the water column for fertilization. In oysters, fertilization takes place in the shell. As oysters get older, they produce more offspring. The larvae are relatively large when they are released and they attach to a suitable growing site quite quickly. How quickly and at what distance from the reef is the subject of the research. The capture of oyster brood for cultivation should then take place in the vicinity of the reef.

What is special about this project is that nature organizations such as Zeeuws Landschap and Natuurmonumenten are also participating. Pascalle Jacobs: “For us as lead author, it is exciting to have the growers and nature people sit at one table and to notice that they learn from each other.” That is not easy, according to Jacobs, because in the past they were usually opposed to each other. Now, however, they have common interests, as it is essential for both the growers and nature that a sustainable reef is created that has a protected status.

If the project continues, HZ Discovery will certainly pay attention to the methods and outcomes of this project.

Mussel farming

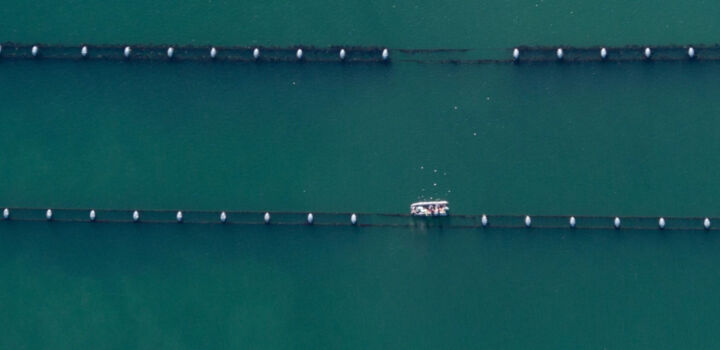

The Aquaculture lectorate is also involved in three projects that investigate whether mussel farming is possible in the North Sea. Wind farms are being considered because there is no sailing there; the Voordelta functions as a testing ground. “The mussel sector indicates that there is room on the market to sell more mussels,” says Jacobs. “But,” she adds, “the Zeeland Delta is full. There is no room for farming.” The transition from the Oosterschelde or Grevelingen to the North Sea is no easy task, Jacobs explains. “The conditions at sea are more turbulent, you have to go there with other boats. Wind farms are further away, which means that as a farmer you cannot watch the mussels grow every week. In addition, we do not know whether there is enough food.” These considerations provide interesting questions for the research that are addressed in the projects.

A project that is coming to an end is a trial to test different methods of hanging cultures in the open sea. The location of the pilot was the Voordelta, an area with a lot of dynamics. Jacobs: “And then the chosen location within the Voordelta was extra rough.” The project will end in 2025 and has had many setbacks. “Disaster after disaster,” according to Jacobs. Because the area has a Natura 2000 status, permits had to be applied for that took a long time. After the installations of the hanging cultures had been installed, a ship sailed into the ropes and everything was lost. Then they rebuilt everything and a lot of damage was caused by the weather and wind. “A bit of a shame,” Jacobs thinks. “Fortunately, the project has been extended for six months in which we will mainly measure a lot to know where the conditions are favorable if you are going to try it again.”

“Mussel farmers are used to keeping a close eye on their cultivation,” Jacobs explains. “They catch mussel spat, remove the small mussels from the ropes at a certain point and put them in a sock. This is a lot more difficult with possible cultivation in wind farms. In addition to the fact that the boats that are currently used are not suitable for the open sea, the wind farms are too far away, making it too expensive to sail back and forth often.” The farmer should be able to monitor the growth of the mussel culture remotely.

The Volta project was started with this idea in mind. The aim is to develop a model that predicts mussel production based on data that is measured every day, such as temperature and food availability. The farmer then decides on the basis of the model whether interventions are necessary. “Wageningen Marine Research (WMR) and we, together with growers, have collected a lot of data from the Wadden Sea and Oosterschelde about the growth of mussels. We have used this to create a model and the intention was to validate the model with the data from the project in the Voordelta. Only due to the setbacks in that project we have little data available.”

A second, supplementary model is being developed together with the Data Science research group. “This also requires a lot of data,” says Jacobs. “And that should also have come from the project in the Voordelta. The aim is to predict mussel production with the two models.”

For the last project on mussels, we return to the inland waters of the Oosterschelde. “Farmers keep a kind of notebook each year to record the results on certain plots,” says Jacobs. “They can then look back to see that one plot did well in the spring and another in the summer and base their decision on whether to move mussels.” The notebook has now been digitized. They enter their data on the growth of the mussels using an app on their phone. “One of the users of the app wanted to know in advance where he could take his mussels to let them grow quickly. We are now busy making maps on that app that indicate the growth potential in the Oosterschelde based on satellite data and a growth model.” The maps help the farmers make decisions about where to put their small, half-grown or large mussels. A major improvement according to Jacobs. “Instead of having to look back through their notebook afterwards, the farmers now know in advance what the best growing locations are.”

'The one from Texel': Pascalle Jacobs

When she couldn't find her way after her studies in Forest and Nature Management in Wageningen, Pascalle Jacobs returned to Wageningen for the Master's in Management of Marine Ecosystems. She did her graduation project at IMARES (now WMR) on Texel. She obtained her PhD at the same institute for research into the influence of young mussels on plankton in the Wadden Sea. When IMARES left Texel, she found a job at the neighbouring NIOZ. There she worked on many different studies that often focused on the interaction between shellfish and plankton. More than three years ago, she was asked to apply for the position of coordinator at the Aquaculture lectorate. She still lives on Texel, from where she works remotely part of the time. "I'm always announced as 'the one from Texel'," she says about it herself.

Aquaculture in Delta Areas

The Aquaculture in Delta Areas lectureship supports entrepreneurs in the aquaculture sector by investigating their knowledge questions in a practice-oriented way.

Read more about the lectorate